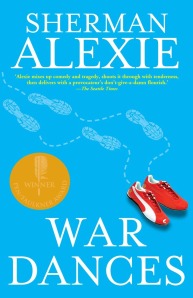

Sherman Alexie, War Dances

Somewhere in the middle of the title story of Sherman Alexie’s PEN/Faulkner Award-winning collection, War Dances, the narrator finds himself standing in a hospital corridor listening to an ageing Native American man he has never met perform a healing song for his dying father.

Somewhere in the middle of the title story of Sherman Alexie’s PEN/Faulkner Award-winning collection, War Dances, the narrator finds himself standing in a hospital corridor listening to an ageing Native American man he has never met perform a healing song for his dying father.

In another writer’s hands the scene might be poignant, a moment in which the fragile bonds of culture are reasserted, however briefly, between two generations of a dispossessed people. Yet Alexie is too intelligent – and too funny – a writer to give way to anything so simplistic or affirming.

Instead he lets the scene play out as comedy, a transaction in which all concerned – the narrator, the old man, his long-suffering son – play their parts in a highly self-aware drama of mutual benefit.

It’s a remarkable scene in a remarkable story, at once sly, tender and blackly amusing, but it’s also a textbook example of what makes Alexie such a fascinating and unpredictable writer. It’s a quality equally evident further on in the same story, when a section entitled ‘Exit Interview for my Father’ is derailed by a poem by the narrator, in which the father is reinvented as a man of strength and flinty native wisdom, before being undercut again by the narrator’s admission almost every detail in the poem is fiction. For by so doing Alexie denies the reader the easy satisfactions of much literary fiction, preferring instead to highlight the ways in which life – like art – is a complex interplay between performance and truth.

This awareness of the contradictions of identity, and of the complexities involved in telling the truth about them has long been at the centre of Alexie’s work. Whether in novels like Reservation Blues, a book that blended past and present, traditional culture and rock and roll to explore the complexities of Native American identity, or his most recent novel, the wonderfully sardonically and ambiguously-titled The Absolutely True Diary of a Part- Time Indian, which drew on Alexie’s own adolescence, Alexie has demonstrated a rare capacity to understand the difficulty his characters face in crafting new identities for themselves when old ones are so readily available.

These same questions animate many of the stories in War Dances, not least the title story, which plays disarmingly with the narrator’s relationship to his Native American heritage. But it is given equally ironic form in another of the collection’s highlights, ‘Breaking and Entering’, in which a man accidentally kills a black teenager who has broken into his home. When the case becomes the flashpoint for racial tensions in the neighbourhood he responds not by apologising, but by demanding the press stop calling him white, when he is in fact Spokane, thereby transforming himself in one fell swoop into “the most hated man in Seattle”.

Similarly in ‘The Senator’s Son’, the son of a successful politician is driven to seek out a childhood friend after recognising him as one of the victims during a homophobic attack, only to be confronted by the unsentimentality of his victim, while in ‘The Ballad of Paul Nonetheless’ an ageing vintage clothing tycoon finds himself seduced by the possibility of appearances.

Yet this playfulness is undercut by other, darker currents, not just questions of mortality, but an awareness of the cost of fear and its commensurate, shame, as in the poem that opens the collection, ‘The Limited’, in which a man gives way to the aggression of a stranger who swerves at a dog.

The result is a collection that is at once darkly witty and oddly tender, sophisticated yet conversationally direct, and which, perhaps appropriately, is simultaneously a brilliant performance by a writer in full command of his powers , and a deeply personal dissection of the illusions of masculinity.

Originally published in The Sydney Morning Herald, 6 November 2010.

Trackbacks & Pingbacks